Dates: 5th July – 11th July

Woomera to Coober Pedy: 575km

Total distance: 2486km

In Woomera we had to make a decision about which route I should ride to Coober Pedy – continue straight up the busy Stuart Highway for another 365km or take my preferred, longer and more interesting route though Roxby Downs, back to the Oodnadatta Track and via William Creek to Coober Pedy. The main issue was waiting for the dirt roads to reopen after the flooding. At this time, two of the roads I needed to take were classified as open only to 4WD vehicles under three tonnes and not towing anything. This excluded one of the team vehicles and reluctantly we decided that I would have to take the Stuart Highway.

I decided to take a much needed day off the bike to visit Andamooka, an infamously wild and remote opal mining town near the northwestern shore of Lake Torrens. It would also allow an extra day for the roads to dry out and maybe there would be a chance to take my preferred route.

When opals were discovered in Andamooka in 1930, it became renowned as a frontier town, linked to the outside world only by rough tracks weaving through the bush and open sand dune country. The town however has more recently cleaned up its act, particularly after the connecting road was sealed in 1996.

Arriving in the main street, the cafe to our disappointment, was closed. However, we met the proprietor, Peter Sach, who was passionate about his community. He was only too pleased to educate Gelareh and I about some of the town’s history and the art of noodling (fossicking) for opals. Peter’s family originated from Czechoslovakia, immigrating to Australia after the Second World War and arriving in Andamooka soon after that. Having lived in the town for about 60 years, we were fortunate Peter could spend some time with us.

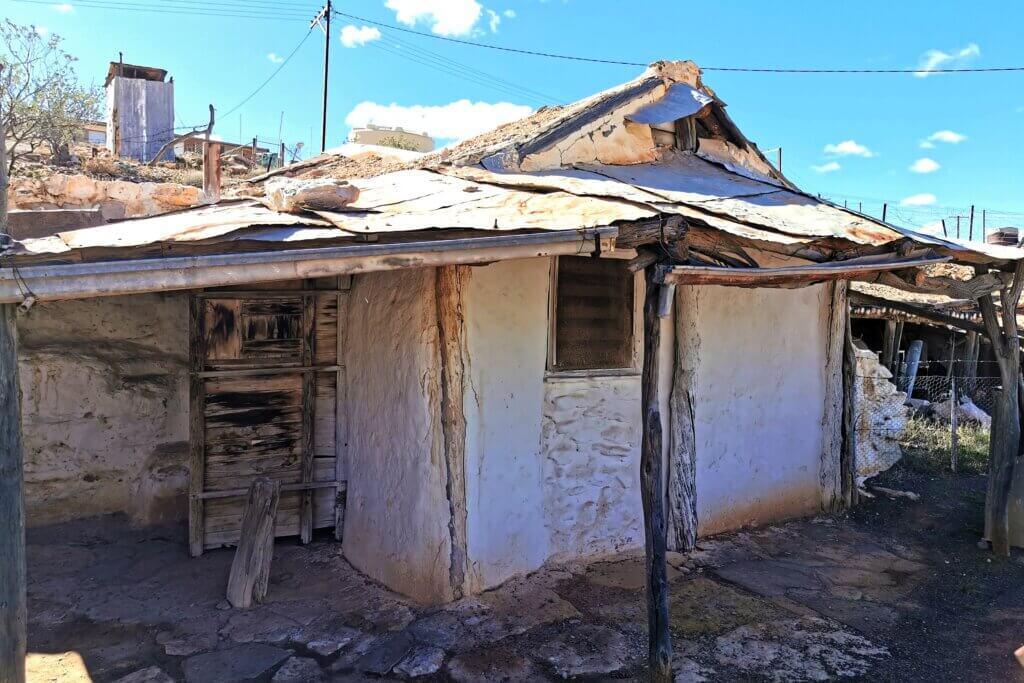

Peter explained that the crumbling ruins opposite the cafe and community hall were the original general store.

Compared with it’s better known opal mining cousin, Coober Pedy, Andamooka’s opals are less prolific but generally more valuable in quality. After a quick demonstration of how to noodle (search for opals), Peter took us out the back of the community hall (a building he and a team of locals dismantled in Maralinga, the materials transported to Andamooka and rebuilt) and pulled out a selection of the opals he has found, cut and polished over the years.

While Coober Pedy is famous for its underground buildings – a sensible design to escape the extreme heat – the traditional homes in Andamooka were semi-above ground; mostly the floors were below ground-level and the walls were dug into surrounding rock. Roofs were made of brushwood and tin. Most traditional dwellings in Andamooka have been replaced by more contemporary homes however a few have been preserved as a reminder of the history and characters of the town.

All around the town, population about 450, were the distinctive white and ochre-coloured mullocks – the diggings that remain once miners have extracted the opals. The cemetery was an interesting place, showing the cultural diversity of the opal mining town.

I was still hopeful that the Borefield Road that connects Roxby Downs and the Olympic Dam mine site with the Oodnadatta Track, would open for us (legally). I noticed the weather forecast had improved and while the track still had the same official classification, the wording of the restrictions had changed. I contacted the Department for Roads and Infrastructure for the region and found that the team could drive the track. We returned to Woomera, where I stopped cycling and I reverted to my preferred plan – Borefield Track, Oodnadatta Track, William Creek Road – to Coober Pedy.

DAY 25 | 107 KM

I set off from Woomera, buoyed by the fact that I was able to cycle my preferred route. It would have been a simple day’s ride if not for the strong headwind. I really struggled through the treeless landscape. The 12cm wide tyres are not great on tarmac and into the wind. The main respite came when I reached the patches of bushland where I could get some shelter from the wind. The BHP-owned Olympic Dam mine is the fourth largest copper deposit and the largest known single deposit of uranium in the world. Traffic between Roxby Downs, where many of the employees reside, and the mine site was so busy, it was like I was back on the Stuart Highway. Just beyond the mine I turned on to the Borefield Road and 15km after that marked the extent of the mining lease. The road was fenced for a few kilometres after that making it difficult to find a decent bush campsite.

DAY 26 | 102 KM

I sprinkling of rain overnight wasn’t enough to affect the road surface and to my delight, a side-tail wind helped to propel me towards the Oodnadatta Track in good time. The Borefield Road appears to have received its name from the string of bores lining the unsealed track for most of the way.

The landscape was a mix of sand dune country and gibber plain. There was a lot of surface water on either side of the road, but fortunately, the road itself had little more than a few puddles to negotiate.

The junction of the Borefield Road with the Oodnadatta Track is just 68km from Marree! I had pedalled over 800km over eight days, down to Port Augusta and back to avoid the flooding and only progressed 68km west! Diverting south and keeping to the tarmac was of course the right decision at the time because there was no guarantee when the Oodnadatta Track would open. We could have been holed up in Marree for two or more weeks and we needed to reach Coober Pedy by 11th July to effect the change over of filmmakers.

DAY 27 | 84 KM

Reaching the Oodnadatta Track, I was back to following the Old Ghan Railway line. We camped beside the ruins of one of several bridges. I wanted to take this route a little easier to appreciate some of its many features, but it was back into a headwind and progress was laborious all day.

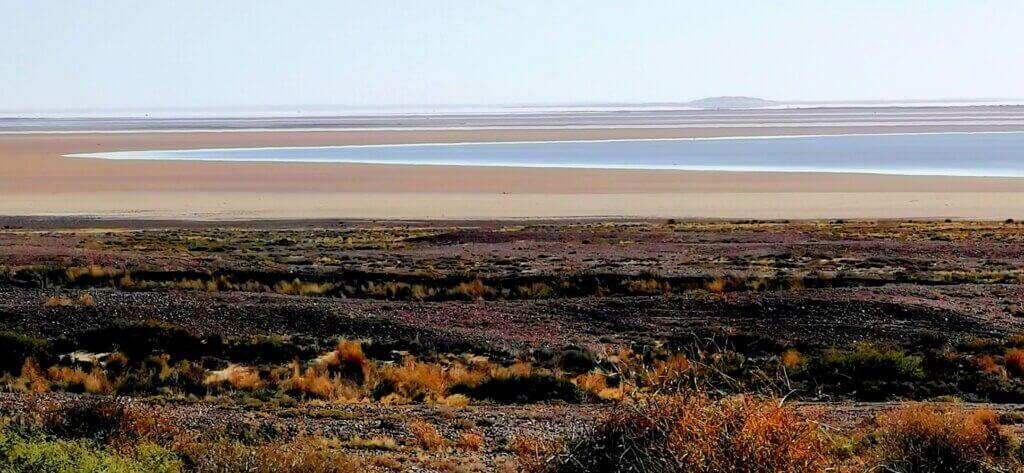

The first stop was Lake Eyre/Kati Thanda South. Amazingly, Lake Eyre was filling fast due to the wet year. I found myself gazing over a bright blue inland sea and plenty of birdlife. Lake Eyre doesn’t fill often, so this was a real privilege.

The Oodnadatta Track was not only the route of the Old Ghan, it was an Aboriginal trade route. Many of the early European explorers employed local Aboriginal people to assist them to find water en route, so it is by no coincidence that the explorers’ routes followed indigenous routes, and the railway tracked these paths.

The highlight for the day was diverting to see the Bubbler mound springs. The artesian water bubbling up from the Great Artesian Basin were essential to First Nations people, animals, and explorers like Stuart to sustain life as a reliable water supply in Dry seasons. It will be no surprise that that springs are the focus of Dreaming stories, being central to sustain life in times of drought.

The Bubbler Spring once roared, throwing twisted bubbles half a metre high. There are stories of old men whispering a special chant to this spring to make bubble out higher and louder. Once the settlers came, many things changed. A tree next to the spring representing an ancestor in the Snake Creation Story was cut down and used for firewood. There was more stress on the water source as it was used to support the settlers and livestock as well as the native animals and Aboriginal people. The water pressure was reduced and the twisted bubbles have disappeared. As the First Nations people lost control over their country, languages were lost and people could no longer live on their lands. Caring for the country became difficult. These days, there is a revival going on and the situation is reversing, though now with Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people sharing ways of living on this land.