Days 61-62

Dates: 10th – 11th August

Tjuntjuntjara

Total Distance 2023: 3830km

Total Distance (2021 + 2023): 5358km

Tracking map: https://z6z.co/breaking-the-cycle-australia/ (access the tracking map for the 2021/23 journey)

While organising this expedition I learned about the Spinifex people, or Anangu, whose homeland is in the Great Victoria Desert. These people were displaced following nuclear weapons testing (Emu and Maralinga) and during the missionary era. I was fascinated to read of their story of self-determination to return to their homelands and wanted to learn more.

BACKGROUND

Tjuntjuntjara, where the Spinifex community now lives, is 650km north east of Kalgoorlie and one of the most remote communities in Australia. Tjuntjuntjara is a closed community, but after persisting for months in an effort to connect, I succeeded and, liaising with the Managing Director of PTAC (Pauplyala Tjarutja Aboriginal Corporation), the Elders approved our visit.

The Spinifex people have lived in the Great Victoria Desert for at least 600 generations; scientists have found evidence dating back 25,000 years. Missionaries began living on the fringes of the Great Victoria Desert only a couple of generations ago. Cundeelee Reserve was originally set up in 1939 as a ration station, principally to draw the Spinifex people away from the Trans-Australia railway line. A more formal mission was set up there in 1950. This was about the time the British began atomic weapons testing at Maralinga, a part of the Spinifex home territory. By 1952, about 130 people were drawn out of their homelands and sent down to Cundeelee.

By 1976 there were 250 Spinifex People and 50 Europeans living around Cundeelee. There was a school, store, office, kitchen and some staff houses. Aboriginal people lived in “bush camps” that shifted around the settlement.

Cundeelee was closed in the mid-1980s due to lack of water and people moved to a newly established town at Coonana, previously a marginal cattle station. The Spinifex People did not want to go there. They wanted to return to the Great Victoria Desert but their wishes were ignored by government officials. Coonana was closed in 2013 when the government withdrew funding for essential and other services.

The movement back to the homelands started in around 1984. A group moved out and camped at Double Pump bore on the Nullarbor Plain. Eventually funding for the bore at Yakatunya was granted and established on the southern edge of Spinifex Country. In 1985/86, after a Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests, the Spinifex People received some compensation. They used the money to put down bores and airstrips at Tjuntjuntjara and Ilkurlka and made 500km of tracks through the heart of their country. In 2000, the community were granted a Determination of Native Title over a 55,000km square area of the Great Victoria Desert.

The Great Victoria Desert is extremely remote (as I found out when crossing it via the Anne Beadell Highway) and not suitable for pastoral or mining development so the contact between white settlers and local Aboriginal people happened much later than elsewhere in Australia. Spinifex people were not consulted and many were not warned or evacuated before rockets were launched from Woomera, South Australia, shot overhead from 1947, and the atomic tests that shook Emu and Maralinga from 1953.

When I arrived, accompanied by the support team, in the dark (about 5.30pm), on the 9th August, acting CEO for the community, Jon Lark lead us through the dusty streets, me avoiding the pack of dogs that threatened to nip my ankles, to “The Barn,” visitors’ accommodation that was our home for the next two days, courtesy of the community.

The first afternoon of our stay, Mark and I were taken on a “connecting to country” excursion with some of the Women Rangers, organised by Nadia who facilitates the Women’s Ranger Programme. This programme ensures women are involved in the traditional and sustainable management of their land while also bonding culturally by telling stories and sharing activities. The Ranger programme is continually evolving and considered essential to equip men and women for the future, to keep their culture strong and provide social support.

We drove about 30km along some narrow tracks to a salt lake. I helped collect firewood for the women’s fire on which they cooked one of their favourite delicacies – kangaroo tails. It was a time to chat and meet some of the women. I particularly enjoyed talking with elders, Ursula and Shona, while the kangaroo tails were prepared and roasted on the fire.

Tjuntjuntjara has a transient community of around 200 people. There were a lot of community members away when we arrived, mostly attending funerals. Still, there were enough people there for us to experience and learn much about their way of life.

On day two of our stay, I offered to give a talk to the students at the community school. The school was established in 1997 after community members demanded a school for their children. Up until then, parents, in order to have their kids attend school, would have to live in Kalgoorlie or Coonana. In the first year, the school was funded by the profits from the community store, until eventually the state education department agreed to part-fund the school. By the third year, the Education Department recognised the school as an essential facility, needed by the community, and employed three full-time teachers. Student numbers were initially about 15, but that can build up to 40 students.

The morning I gave my talk there were just four students – many were away with their families attending the funerals. The children were delightful, although probably a bit too young to fully comprehend my story, illustrated with images and videos. I gave the talk sitting with them in the library and about half way through they started sitting with me, helping to forward the photos, wanting hugs and fiddling with my hair as I spoke! After the presentation, they loved taking a quick ride with me around the block. Apparently they received their bikes as reward for good class attendance.

The Spinifex Arts Project is being run at the Arts Centre, built about a decade ago. The project began in 1997, initially to record and document ownership of the Spinifex area within the Western Australian side of the Great Victorian Desert in the lead up to their successful Native Title Claim. The Spinifex People are responsible for several significant Western Desert stories that traverse the land area and involve close adherence to complex traditional protocols. Painting country is intimately connected with their cultural protocols and is a way of maintaining culture within the Western Desert and the wider community.

Men and women paint different subjects, the women’s paintings tend to be very colourful whereas men’s works usually comprise of only a couple of different colours.

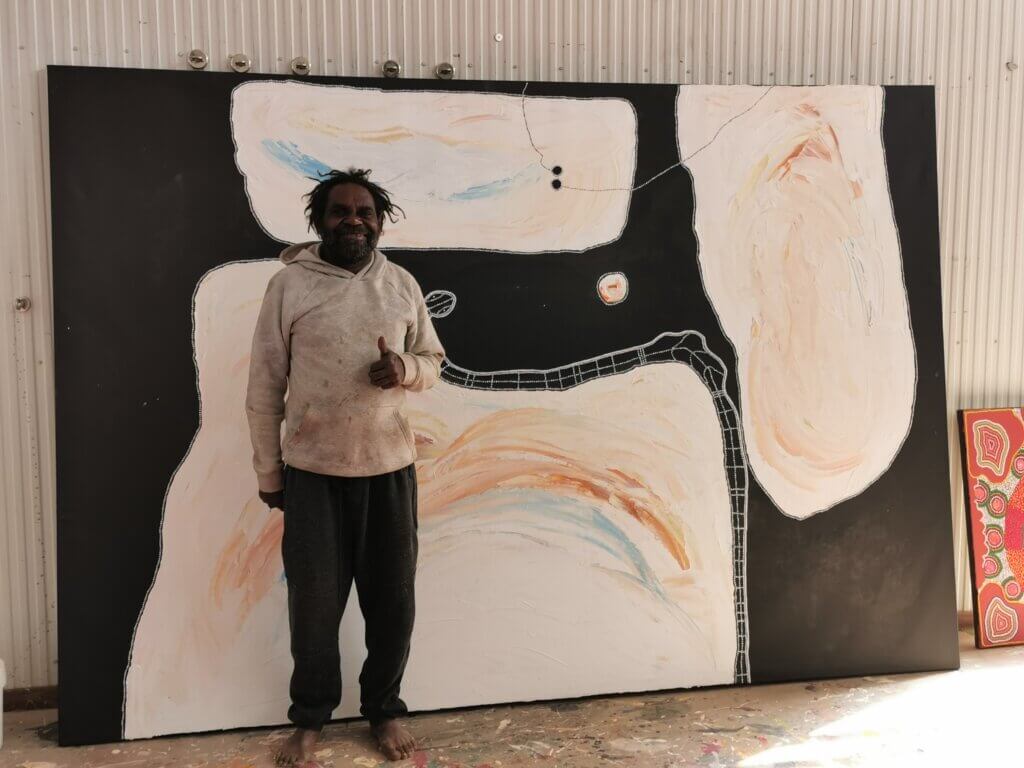

Mark and I only managed to capture the tail end of a painting session (Fridays are half-days) and wished we could have spent more time. We were lucky enough to meet some highly respected elders and renowned 2021 Telstra prize-winning artist, Timo Hogan.

Perhaps the interactions that have affected me the most were those with two members of the Rictor family, the last Australians to live a nomadic existence. In 1986, Noli and his brother Kunmanara (this is the name used for anyone who has just lost a close relative, it is not his given name), along with five other members of their family walked out of the desert and away from a traditional nomadic life. They were found by a group of elders in bushland near Ilkurlka.

The brothers had been working away quietly and intensely on their incredible artworks in one corner of the art centre the whole time we were there, but not long before the session ended they agreed to meet us.

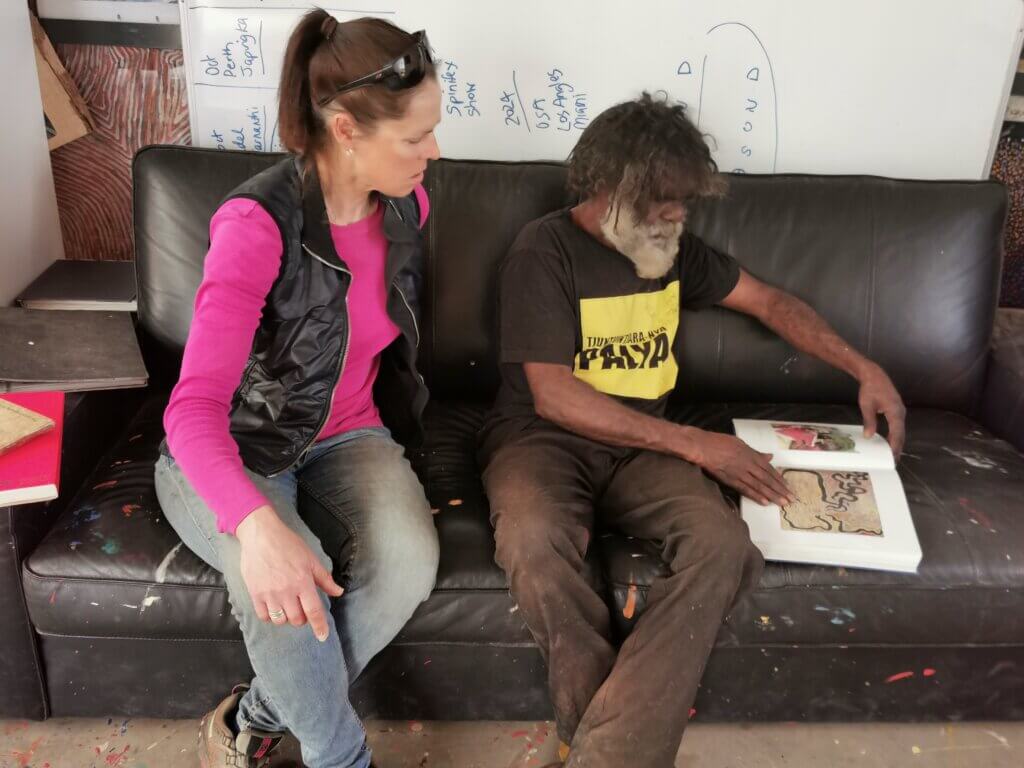

Noli in particular, was very quietly spoken – he was shy and not confident about speaking English, but he wanted to connect. I felt quite overwhelmed and incredibly moved as I sat with him as he flicked through the pages of an art book as a way of communicating, to show Mark and I works by his family. I can’t imagine the transition they must still be working through, from living solely off the land, naked, and then to be slowly introduced to a very different world. I wondered how they see the world. Their perceptions must be so different to mine / ours. Art must play a very important part of their lives and having to adapt to living in a community.

That afternoon, Jon Lark (Acting CEO) took Mark and I on a short drive to take a look at one of two old army trucks that were used to transport building materials and people from Coonana to start the new community at Tjuntjuntjara. Jon and his friend, Ian Baird, had been involved in facilitating the transition from Cundeelee to Coonana to Tjuntjuntjara. Jon speaks their language, Pitjantjatjara, and after almost 40 years of living with them (though he is from Kangaroo Island, South Australia), few non-Aboriginal people would know more about the Spinifex culture than Jon. During our interview, Jon emphasised how strong the spirit and culture is in the Spinifex community. The reason the transition to Tjuntjuntjara has been so successful is that all decisions are community-lead. Their success is because of strong leadership from the elders that both maintains a healthy, traditional culture and language and prepares its people for the world outside their community.

THE RATION TREE

Mark’s and my final excursion in Tjuntjuntjara was to travel with some elders to visit the Ration Tree. As mentioned in the introduction, missionaries living in the margins of the Great Victoria Desert chose a strategic location on a route where nomadic Spinifex people would frequent (walking path) to place rations and clothing to draw them out of the desert – to convert them to Christianity, transition them to a very different “Australian” way of living and clear the desert for the pending weapons testing.

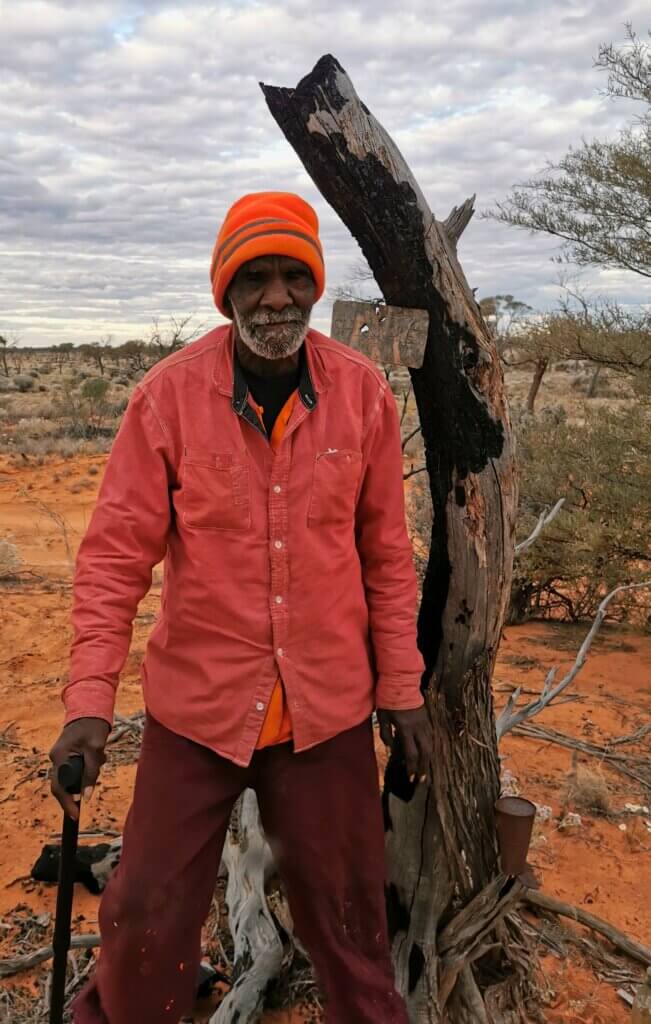

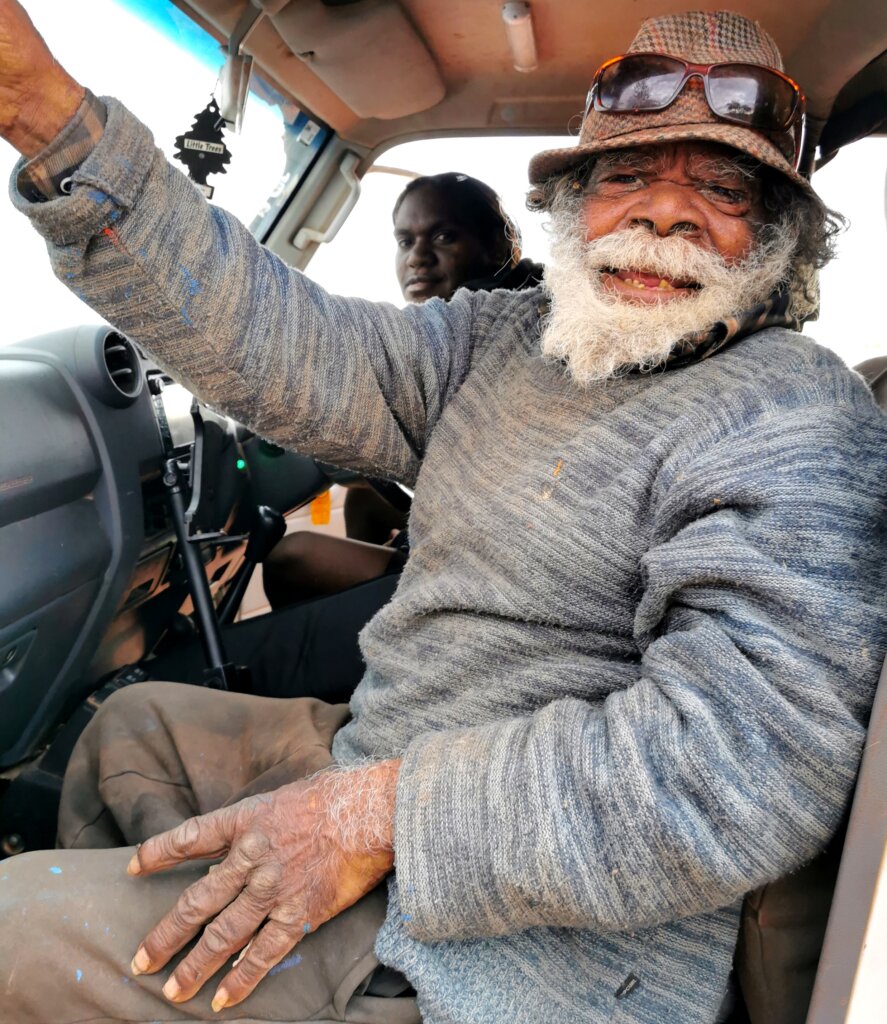

When Nadia (Women’s Ranger programme) asked who would like to come and tell us about their experiences at the Ration Tree, several elders volunteered. I was honoured – they really wanted to tell us their story. Accompanying Nadia, Mark, Janine (ranger) and me were Byron Brooks, Ned Grant, Maureen Donnegan and Ursula – the women both helped with the translation but were happy to take a back seat.

Beside the Ration Tree, Byron, who was a teenager when he first saw the ration station, recalled what happened. They would walk down their usual path out of the desert and collect the rations and clothes beneath the sign. There were many of his people camping in the vicinity, many campfires lit up the night sky. Then he pointed to another track leading west from that point. That was the direction the missionaries came from to take them away to Cundeelee. He recalled a train journey where some people lit a campfire in one of the train carriages to keep warm.

Ned was not very mobile and needed to be wheeled across the sand in his chair. He too was a character with a similar story. Ned said that, while his Traditional beliefs were most important to him, he still keeps a Bible at home. Earlier, Mark and I had met him at the Arts Centre and he was very keen to tell us his story. Ursula did a great job translating as their English was very difficult to understand.

Returning to the community, there was a lot to process. It had been an emotionally charged two days for me that are probably going to be life-changing. It was really only a glimpse into how different their culture is from mine but leaves me wanting to learn more.

I thank the community, especially the elders, PTAC – Jon Lark, Adam Pennington, Nadia Hamson, Jelaine and Lois for hosting us and making our stay in Tjuntjuntjara a very special one.